Enigma Sessions: Lex Kiefhaber on Climate Tech and AI

Using market forces and technological advancement to combat climate change

These two things are true simultaneously - there's more energy, focus, money, and technological advancement around the world of climate tech today than there ever has been and we are also careening towards disaster faster than we ever have been. - Lex Kiefhaber

For the first Enigma Session, I have a conversation with Lex Kiefhaber about climate change, climate technology, and AI. Lex Kiefhaber is the host of the Who's Saving the Planet podcast and the former CEO of United by Zero. He's spoken to over 150 individuals about how they are helping to combat climate change. We dive into economic and societal forces to grasp the challenges in fixing the climate along with what's required for good solutions. We talk through how AI is helping to advance climate technology and how it is being used today.

Note: This conversation has been edited for clarity and brevity.

Eric Koziol: Great to have this discussion Lex. Give everyone else a little bit of background about yourself.

Lex Kiefhaber: I came to the world of climate tech in a very circuitous way, which is through the bar, not the way that people become lawyers, but the way that people get a drink. I was a wine professional in my 20s and enjoyed that very much. I felt the calling around 2013-2015 when some of those IPCC reports came out that really were sounding the alarm again, but for me, that was the first time that I really heard that message and that's when I decided that I wanted to dedicate the majority of my working life to this issue of survivability on Earth as we know it. So I did what everyone did is at that point, which is go to business school.

I needed to understand how to transition from the hospitality industry into something that would be at least a little bit closer to the world of climate technology and entrepreneurship. I did that and then I worked at a high growth startup to learn the practical applications of the things they teach you in business school and that grew very quickly, then stalled, and then they laid everyone off. This was my second moment of the journey. The first was let's go explore this thing. The second is now that you have achieved some degree of skills, life has presented you with an opportunity again to refocus yourself.

That's how I took it, and that's when I started the podcast because I wanted to get into the world of climate technology entrepreneurship and how that applies to the everyday consumer. The person on the street as opposed to a technologist or an engineer. The way that I thought to do that was to create a platform where I can have discussions with people that are actually building the technologies, the platforms, and the products that will shape that future. I started Who's Saving the Planet and on it's continued on to this day. It's been a fantastic opportunity to have discussions with people that I have no business talking with. It's really afforded me a great perspective. One that's a mile wide and in lots of places like an inch deep. However, I've dove into different areas of this that I find to be really compelling. The breadth of the people that I get to talk to is fantastic.

Eric: As you've had these discussions with over 150 individuals, what are the biggest challenges you see in tackling climate change?

Lex: There's no one answer to that question. So I don't think there's a monolithic answer to what our biggest challenge is, since it depends on what your vantage point is. What your perspective of the world is. From mine, I think the biggest challenge, based on my sort of lived experience and the perception that I have from the people I've spoken to, is the whole idea of we need to continue to grow the economy at three to five percent a year and we need to sell more things. That the winners will be governed by profit margin and by market share. That cycle precipitates so much of the incentive structure that makes it really, really difficult to change course, to sort of realign what we think is valuable. The wins are so compelling because they can be measured by the material gain is obvious. We as humans are short-sighted and so being rich in our lives is a very powerful motivator for so many people. The entrenched interests are incredibly powerful. So you put all those things together and this sort of idea of capitalism is the engine that drives us towards making an increasing number of things and selling them for an increasing number of dollars regardless of the impact that has on the planet, the ecosystem, and the people on it.

Eric: Are you saying that our shared resources on this Earth aren't fully accounted for, that they're not valued in the correct way, or something else?

Lex: There are people that have said that so much better than I have. Naomi Cline's book This Changes Everything is really sort of the foundation of this thinking for me and many have built on it. But it's not that complicated a principle. We have a finite amount of resources on this planet and as we dig them up and use them that pool of resources, it becomes exhausted faster than we can replenish them. We see that with the way that our forests are burning and we see that with how we are burning fossil fuels and creating carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. It's an exhaustive means of being part of this ecosystem. It's extractive and it is parasitic to sort of the idea of a harmonious Earth, but it's incredibly profitable. And that therein lies the problem, right?

Eric: Well how can we balance these two seemingly opposing forces?

Lex: Yeah, there's an ironic twist to the story at the end. It's that while capitalism is the thing that has precipitated all this climate catastrophe, I think it is probably also the only thing that could get us out of it as quickly and completely as we need to be. It's not going to be a system like communism or a top down dictatorships or what have you. There's no political solution that's going to work. There's no altruistic solution that is going to work. It's going to be a changing of the incentive of market forces. Such that we decide that sustainability is the biggest profit center. It's the place where the most people will go to buy the most things and that living on Earth in harmony is the best business decision. If we can do that, it unlocks all of the other aspects around removing real blockers for legislation. Money is pouring into this space at an even faster pace than we've seen before. More options being available for consumers so that they reinvest from the bottom up into these solutions in a way that it is funneling more and more money through the system to not die.

If we can figure that out, I do think capitalism is the perfect system for completely changing the things we decide to make and that's where there's been examples of this in the world before. That's the only thing that we've seen work fast enough, with perhaps the exception of war. And I don't advocate for that. So if we can find a way to align the paradigm structure necessary to create a sustainable world with the incentives inherent in capitalism, perhaps we can build a future that will be habitable for humanity.

Eric: Yeah, that's a multifaceted problem with an interrelated web of issues. Issues where no single solution is going to be the answer. When you've heard of all these different solutions from the 150 plus people you've spoken to, what solutions look like a slam dunk, and what will kinds of solutions look like long shots for actually helping to abate this problem?

Lex: The thing you just said, it's a multifaceted and interconnected problem. There are no silver bullets. There are no slam dunks where it's like, once fusion technology exists, we will have an infinite supply of energy with no negative effects or no emissions. That doesn't exist. When I've spoken with people, the perspective is often something like let's take a siloed problem and let's see if we can approach that as a scientist or an engineer would. Starting with here's this problem, how can I fix it? If we can move the ball forward on those individual problems, then perhaps collectively we're going to be able to adjust course as a species.

So the answer to that is 'yes and'. There's lots of things we can cherry pick within that to say here's a cool example. This is how energy storage has progressed, by generations worth of technology in the last five to ten years. Renewable energy is much more efficient than it was. Lots of examples, but none one of those things will be a slam dunk for climate change. We just need to make sure that we're continuously pushing the ball forward on every front. But again against what. I think the against what thing is the thing that makes it so difficult. Often I'll talk to people and say things along the lines of, "hey, you just told me this amazing incredibly optimistic story about how you are creating a way to recycle plastics with an organic compound instead of a machine process, which makes them infinitely usable. So there's no degradation of the plastic water bottle. You can continue recycling and it doesn't go bad and it's also much cheaper and more efficient in the long run." These are great, I love them. However, we emitted more emissions this year than we did last year, which is true from the year before which is true that year before that which is true for the year before that.

There's this big question of what are we doing here? Things are only getting worse. And even the money's pouring into this space and there's more public awareness around it. We are inching and closer to that doomsday midnight hour of survivability as we know it on Earth and that does not appear to be abating. These two things are true simultaneously - there's more energy, focus, money, and technological advancement around the world of climate tech today than there ever has been and we are also careening towards disaster faster than we ever have been.

Eric: If you look at it, even if you could stop all emissions today, we're still probably in a bad space. But there's no chance of that actually unwinding overnight. What's at play for steering us towards making the right decisions?

Lex: If you could stop all emissions today, we'd be okay. That would be alright, there would be catastrophic effects for civilization.

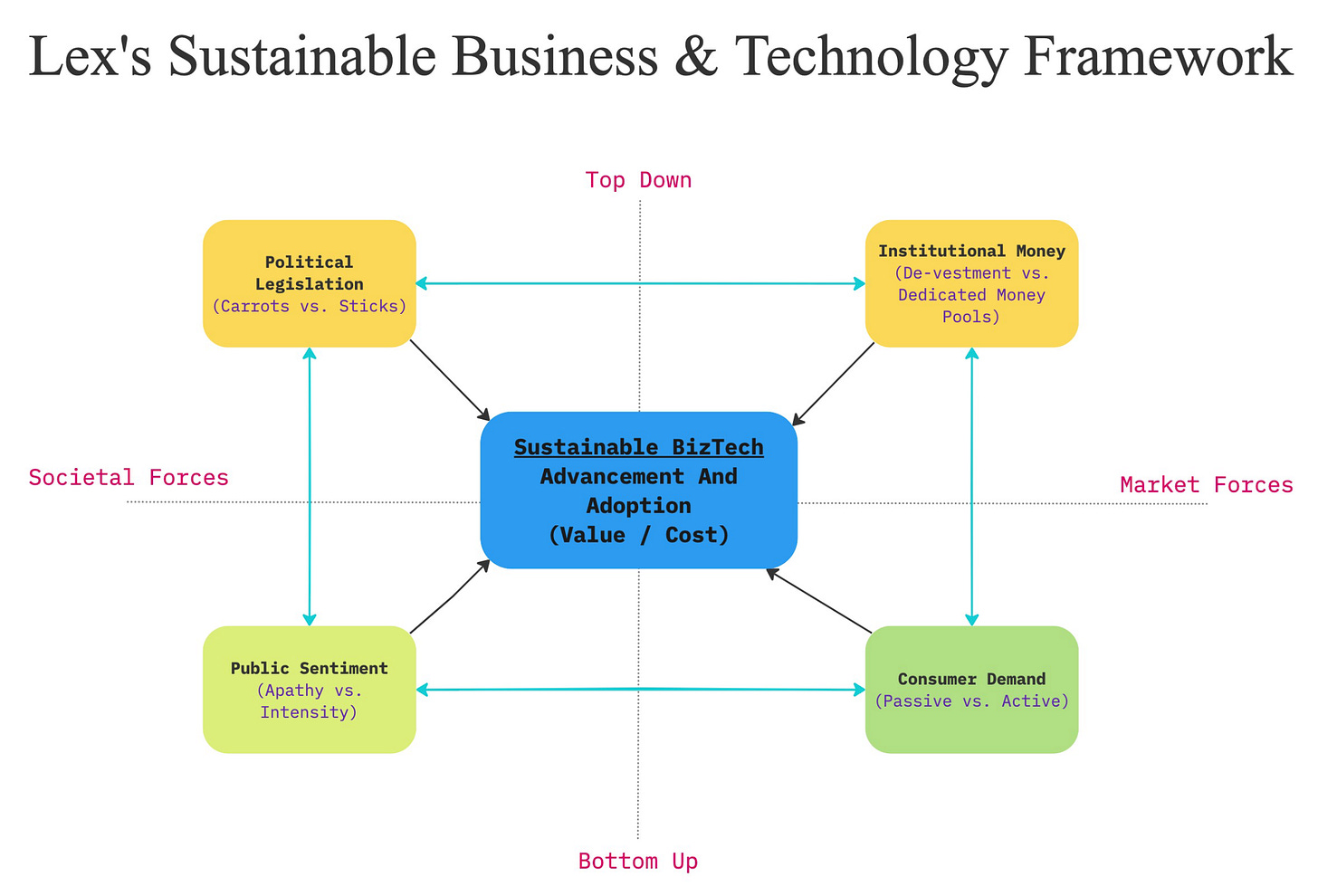

I see this as the five pieces to this question.

Top down market forces. This is mainly institutional money. A lot of things are like ESG and DEI movements are an outflow of them deciding how money is gonna move through the world.

Political Forces. These are regulations and laws modifying incentive structures. These things are pushing us towards a more sustainable world because we think that there's long-term profits to be had or at least new areas of investment. Also politicians to some degree think not dying maybe a good strategy.

Bottom up forces. You have activism which we see more now than we have in a long time. There's a whole variety of movements around the world that are youth led movements. They are creating a more fervent pitch around "let's not die".

Shifts in consumer behavior. This is a laggard. They call this to say-do gap where people are very happy to tell you they'd like to shop sustainably, but they do not follow through in opting for a more sustainable alternative. That's for a whole wealth of reasons. Products are hard to find, they're hard to trust. Maybe it's not exactly you're looking for. They can be more expensive. There's no social costs to choosing the less sustainable thing. Until consumers decide that they want to spend their money on things that are more sustainable, it's gonna be really really hard to have all of these courses catalyzed into something that is going to unlock this shift in capitalism.

Advancement of technology. The advancement of technology is something that can make these things more efficient and cheaper and by these things I mean, all of the things around how we make and use things in the world. All of those aspects can help promote the advancement of new technologies faster by working to unlock barriers and also incentivize investment.

Eric: That's a helpful framework. Following along those lines, from everyone you've spoken to and from what you've seen, where is AI really helping to unlock that technological advancement in this fight against climate change. Where is it actually having an impact? And where is it useful?

When I think about AI as a practitioner and I think about climate change, I think of things falling in three main buckets. One is helping to make things more efficient. Typically this is from better or faster decision making, such as balancing the electrical grid. Second, things that help us predict and better prepare. We're able to assess risk in a certain area and then take actions or mitigations. Third, is to help find better solutions where the search space is too large or too difficult such as finding new materials.

I don't know if that's the same type of encapsulation when you look at these companies and technologies that you think is helping, or if there's a different way to look at it.

Lex: So the big answer to your question, which is kind of the answer to all questions that start with AI, is everywhere. There's no thing that does not have some application for artificial intelligence. That is cool. We're going to go into a couple of specific examples but the other part is that AI is relatively new and so we're not seeing this actually matriculate through the system in a way that has a lot of really tangible wins. It's still a lot on the experimentation side of things. We don't know which one of these is gonna have the biggest effect on emission reduction or consumer behavior or energy storage any of these big questions.

Large Search Spaces

So on places where the search area is so large. There's this company called Chemix and they are creating a thousand different types of chemical compositions for batteries and battery storage for electric vehicles that are dependent on particular use cases and different types of materials and elements in it. Such as nickel and cobalt, but also lots of other things depending on whether you're driving an ATV or a submarine. What they're able to do is use AI to model in this virtual space the myriad of potential physical constructions of batteries and then test them theoretically against their use cases. They can do this virtual lab bench testing before they actually get to the work of building something. That's awesome. That means the process of R&D can be dramatically reduced and made much less expensive. Such that when you're getting to the part of actually building something you have a much better likelihood of building something that's gonna fit that use case.

Another one would be this company Aether Bio which is creating machines at the molecular level. So take for example the idea of lithium mining (we need lithium for batteries). Imagine if you could take a liquid solution, a saltwater solution, and you could at the atomic level extract every molecule of lithium from that solution and then deposit into a specific place, so that you could then create a repository of lithium from this complex solution, without using a tremendous amount of energy for electrolysis. It comes from using a combination of CRISPR with these AI integrated tools for understanding what the correct molecular shape of that molecule should be to go grab the lithium atom and deposit it somewhere else. You could take that idea and say what if we could create titanium and just build it in a way that was more efficient? Or what if we can desalinize water with something that looked like the size of a refrigerator and you can take it anywhere and create potable water wherever you need it? All of this is made possible by the advent of advanced computing and AI. Those are two examples of things from the massive search space.

Predicting

For the predictions space, let's look at things and decide how dangerous are they. The place where I think this is gonna be the biggest impact will be in the world of insurance and we're seeing that now. There's modeling around fire, drought tornado floods. All to determine what is an insurable is a multi-trillion dollar market. Creating some kind of understanding of how climate and weather will impact our built environment will be huge. More directly today, there is a company called Vibrant Planet, which is a bunch of engineers, modelers, and scientists that are creating models around forests, forest regeneration, and forest usage. They're using these types of models to better understand how we should manage our forests, what is at risk, how we should think about the fact that we are losing more forest faster than they are able to grow. Which means that we are going to run out of trees at some point. We will hit that tipping point. So how can we create a model that will inform us about the impact of our decisions today and how we should change those decisions?

Better, Faster Decision Making

The balancing load one is a pretty straightforward one. Scale Microgrid Solutions just raised half of a billion dollars to deploy some of their microgrid solutions. The company is happily named. They're deploying AI to better understand how to more efficiently mitigate for disasters. So if you're a hospital how do you make sure that you have the right kind of energy storage and capacity if something happens.

That's sort of happening across the system, but there's so many entrenched interests. The utility space is arcane, it's so old. If you have somebody come in being like 'hey, we've got a much more efficient way of distributing power', there's lots of people that are saying that's exactly not what we want. We're very happy with the way that power is distributed right now. They have no interest in a more efficient model. What do you do with that? That someone's livelihood that you're saying "great news we're wasting half our power" and someone's like that means you're gonna throw away half my profits or half my revenue.

There's one last one I'll give you called Actual. They're creating massive sim city-ish models of different business choices using AI models. Say you have a trucking fleet and let's say you want to electrify your trucking fleet, what happens if you buy these types of trucks and deploy them and how does that affect your revenue, downtime, and usage. It's cool. It's just a giant simulation of your business use case and they're able to apply that for in-depth decision-making.

Eric: I can see the societal pressure you're talking about in terms of overcoming that but what we're doing is kind of on a collision course if nothing changes? If you keep making the same decisions, you're going to get the same outcomes. If you're not changing the way things are done, I don't know why you would expect different results. While it might be self-interest, to your point at the beginning this conversation, it's really really hard to change when you're looking at different time scales from how people are thinking, right?

Lex: We have seen the world change dramatically, recently. If you think about a number of the technological revolutions that we had just in the 20th century. How quickly the automobile changed the way that we move goods around the world. To the extent that we built roads and an entire infrastructure of utilizing energy changed. That was a couple of decades from the beginning of user adoption to the ubiquity of the world of the automobile. It's within one person's lifetime, you went from a horse and carriage to the automobile being the predominant way of things moving through the world.

You've seen the same thing with air travel. That completely changed the way goods and services are moved around the world and how people can travel. Obviously with the internet, that sparked a variety of revolutions that happen pretty quickly, one after the other. Not only did that change our total system of information sharing and commerce, but then we had mobile technology which changed our relationship with information, commerce, and each other. Then the platform economy changed our way to think about how goods and services can be applied to us as people. All of these things spurred not only billions of dollars of investment and trillions of dollars of market value globally, but there was also shift in how we move around the world. That also precipitated changes in legislation and changed the way the governments moved. There was a change that top down monetary forces. With most of them there hasn't been a big impediment but for the adoption curve of people.

When the internet came around the phone companies couldn't really be like "No! No more internet. We're getting rid of it." When the iPhone came out there wasn't big telegram that said "no absolutely not, we're cutting it down." Unfortunately, what we see with a lot of the technologies around creating and using energy in a way that isn't going to kill us, there very much is a multi-trillion dollar interest that's saying "no, we like taking carbon out of the ground and setting it on fire. We very much enjoy doing that." That is a different dynamic than lots of these other advents of technologies. It creates this conflict where on one hand you do have all of these solutions that are blossoming across a whole variety of different verticals. On the other hand, you have not only inertia of the way things were done but you have a real financial incentive to slow the growth of that transition. I think that is the most interesting question here which is, within that system, how do you change it with the speed and the ubiquity that we need in order to not die?

Eric: If I break down your question differently, there's two big components you're talking about. One is technological solutions that can actually reduce our impact on the overall climate and the second one is around social dynamics and how we actually get people to do things and follow through. It sounds like there's a lot of progress on the actual technology to do this, but not so much on the social side. What I've seen from AI and its applications It's ability to understand, manipulate, and change your behavior at a large scale. For instance, recommender systems in big tech and social media companies. I'm curious if you've seen anyone helping change people's minds using AI to modify social behavior in such a way that's a benefit.

Lex: In theoretical spaces people are trying to gamify. How do we find our way out of the maze of the tragedy of the commons? I don't think that that matters if there's not a direct line between that and a profit seeking incentive. Like you mentioned, Google is very good at understanding what we want, as is Meta, as is TikTok. These companies are fantastically sophisticated. Generally they're not trying to incentivize us to buy less.

Amazon came out with this climate pledge thing. There was a badge they put on products for a brief moment in time. It may still exist. What they were trying to do was signal this is something that you should buy without any underpinning of this is actually going to be good for the climate. One of the criteria was it's packaging needs to be more efficient. So they literally could just pack more stuff in boxes to reduce their overhead. That got you to climate badge. Amazon isn't going to say that you already bought enough things, we're gonna scale back consumption. That's not what Amazon does. The whole system of globalization of productizing China as a way of creating things that are unregulated largely from their environmental impact, from their workforce, from their labor from the amount of chemicals that are produced downstream from their creation, but it's creating this river of cheap shit that we can buy. And we're very much addicted to it. When your question was about who's using AI to combat, or to change the consumption economy, who wants to do that? Who's incentivized to do that that has the reach that would actually have some sort of impact that would be measurable of the societal level?

It's not because they can't. It's not because the technology isn't there. It's not because we aren't going to be susceptible to it. Those things are totally true. It's goes back to that first thing you said - what's the biggest challenge of climate change? Capitalism. If you're going to go and say I'm gonna decrease shareholder value, our stocks will go down because we're gonna sell less shit, but good news you're probably going to live a little bit longer. You're grandchildren may have potable water. It's hard to sell that at the quarterly report. Nobody at Davos is going to believe that. They'll give you a pat on the back, but they're thinking I'm going short that guy real quick.

Eric: To a happier topic. Dirigibles are near and dear to your heart. What is it about these airships that excite you so much?

Lex: I do love dirigibles. They excite me in the same way that having an afternoon where I don't have to speak to anyone and I get to sit alone and read a book excites me. It's not like an active excitement. It is just a slow, calm appreciation of a place and time.

Here's what excites me about dirigibles. They capture this idea of an unhurried life. You're just moving at the pace of the slipstream that's taking you east to west or north to south. It can be absolutely, stunningly beautiful. At a vantage of the world that birds get to see, we as humans don't have the ability to take the world in it that way. They can be so gentle but also so massive in the way that they can move incredible things. It's just a fanciful notion. It's a vision of the future that feels so much closer to technologically advanced but also sort of harmonious. Where they're not really destructive in their progression across the sky. They're not burning fuel or screaming across it. I don't know, I find a romantic. Also, the word dirigible is a ton of fun.

Want to get a remote job at Amazon?

Start reading HackerPulse Dispatch & level up your skills as an engineer.

Get weekly:

Useful Tools & Libs

Best AI paper digests

No-nonsense career boosters

Go 👉 HackerPulse Dispatch